Exploring Real-Life Healthcare Data for Young People with Mental Health Issues

Understanding the journey of young individuals with mental health issues is critical in providing appropriate support. Research often delves into patterns of mental health problems in children and adolescents to identify trends and potential areas of intervention. While longitudinal cohort studies have been a common method in the past, a recent study has taken a different approach by analyzing real-life healthcare data. This article explores the findings of the study and its implications for improving mental health support for young people.

Do prospective studies really tell us much about the real-life use of healthcare? This study uses GP records to assess ‘real world’ use of healthcare services for mental health support in young people.

Examining the Methods

The study utilized the CPRD-Aurum system to capture data from GP practices across England, focusing on patients aged 3-18 who sought help for mental health issues between 2000 and 2016. The objective was to group individuals based on their patterns of GP attendance, prescriptions, and contact with specialist mental health services over the next 5 years using multi-trajectory modeling.

Key Findings from the Study

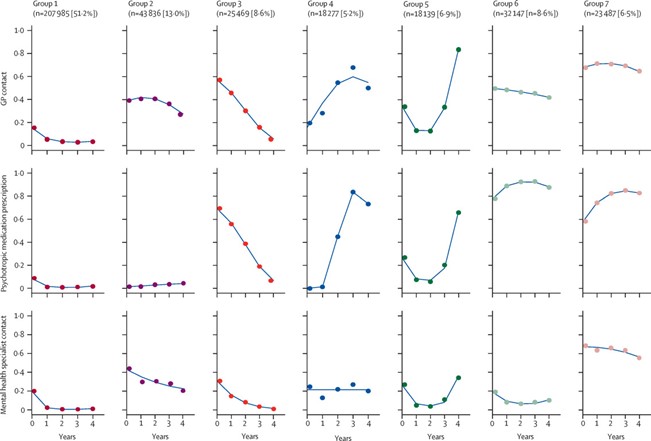

From the extensive pool of 369,340 individuals identified, seven distinct groups were established to represent different service-use patterns over time. Notable findings included variations in prescription rates, sex differences in service utilization, and drastic changes in service use among certain groups over the 5-year period.

This study found that young people who contacted their GP for mental health support between the ages of 3 and 16 fell into one of seven groups, with over half of the sample being categorised by low engagement with GP, specialist services and prescriptions following initial presentation. [View full-sized graphic]

Implications for Practice

The study’s findings can potentially aid in predicting the care needs of young individuals early on, leading to more efficient and tailored interventions. The idea of specialized mental health support to alleviate pressure on primary care services is also highlighted, suggesting the need for dedicated youth mental health services to provide targeted support.

These findings may ‘reassure’ children, adolescents, and caregivers given that 51.2% of children who presented to their GP with a mental health issue went on to have low contact with services.